Animal Activities

Test Yourself!

The Nauo speaking people were at the forefront of colonial intrusion into South Australia. Traditionally associated with Coffin Bay and the Lower Eyre Peninsula, Nauo people came into early conflict with sealers and whalers well before the official colonisation of South Australia in the 1830s. A period of violent conflict with settlers and soldiers in the 1840s contributed to the dispersal of Nauo speakers. Nauo people today are reconstructing the history of their forebears and their resistance to colonial invasion of their lands.

The Nauo language (sometimes written Nhawu) is currently being reclaimed from historical records. South Australian Museum ethnologist Norman Tindale claimed that there were no living Nauo speakers in the 1930s when he made his enquiries. Linguistic research by Jane Simpson and Luise Hercus conducted in the 2000s shows that the Nauo language was part of a group of related languages that includes Adnyamathanha, Barngarla, Kaurna, Kuyani, Narungga, Ngadjuri, Nukunu and Wirangu. Importantly, Nauo is most closely related to the two neighbouring languages Barngarla and Wirangu. This relatedness means that the three languages shared some words and grammatical patterns and clearly differed in ways that allow us to reconstruct a Nauo vocabulary from what is known of the three languages.

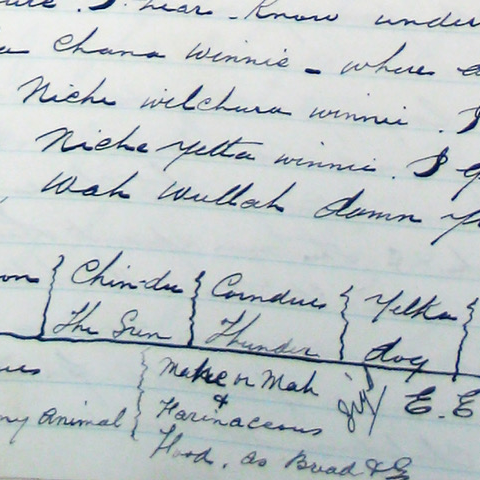

The primary sources from which the Nauo reclamation draws are the diaries, papers and publications of Clamor Schürmann, a Dresden missionary who resided at Port Lincoln in the 1840s. Other colonial agents, such as administrators, pastoralists and policemen, made important recordings of short wordlists, Aboriginal people's names, and place names. These recordings often provide clues to the Nauo language and the cultural interrelatedness of Nauo, Wirangu and Barngarla. Wirangu and Barngarla are also undergoing a language revival process in Ceduna and Port Lincoln.

Test Yourself!

Searchable wordlist