Lesson 10 – Fishing

The Tanganekald people are traditionally skilled hunters and fisher people with innovative traditional methods to secure some tucker. This lesson we will learn about fishing, let’s start by learning about where a family could hunt and how the ruwi ‘country’ was divided.

Traditionally Tanganekald ruwi ‘country’ was divided into many small hunting and fishing territories called karawi or kurawar. These were marked by well-defined boundaries called kinara. Kinara were marked by various geological features, or sometimes took the form of carved sticks with the ngaityi ‘totem’ of the owner. The karawi or kurawar ‘family hunting territories’ were controlled by families who had the sole right to hunt over the area. The head of the family territory was called the kalyanan karawi. These hunting rights associated with the karawi or kurawar were passed down from father to son, and if this succession failed the area would pass to the owners of an adjoining territory who were of the same moiety. A man’s brother had equal right to share such an area subject to a certain deference of a younger brother towards an elder. A younger brother might be given a karawi or kurawar ‘hunting territory’ by someone of the same moiety who had too large of an area.

Fish Traps

Fishing was a major method of hunting for the Tanganekald. Most fishing activities took place in warmer months when the winds died down. To begin the hunt, people would start at a nganamuki ‘lookout’ to spot schools of fish at a distance. Nampulunu is the Tanganekald ruminyeri for ‘a shoal of fish’. Milerum said it was important to never point at a shoal, as the fish would vanish. Instead you must shut your fist and elevate your thumb instead.

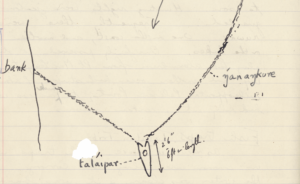

Fishing in the Coorong largely composed of fish traps. Fish traps were often used as it was hard to spear fish in clear waters, unless the fish were in seaweed. These fishing traps were built in the swamps and the shallow waters of the Coorong. They often used natural formations like rock deposits or banks to form part of the trap structure.

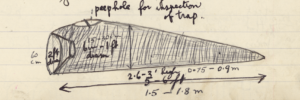

The actual fish trap was woven out of reeds and called a talaipar. It was traditionally made by men (pictured below).

This talaipar ‘fish trap’ was part of a much larger system. The Tanganekald people would used the shore line with constructed ngangkuri and ngaldi ‘walls’ made out of blocks of limestone, mud, sticks, and seaweed to channel fish into the trap. These ngangkuri and ngaldi ‘walls’ stretched out into deep water and were made by both men and women. No organised attempts were made to drive the fish into the traps, the fish would swim in the right direction naturally.

Deadly work! Let’s have a look at some words associated with fishing

Fishing terms

Good work! Let’s have a look at some words relevant to fish nets.

Fish nets and baskets

Traditionally fisher people in the region used hauling nets. These nets are designed to be cast over a nampulunu ‘shoal of fish’ so they would be trapped and pulled out of the water. Set nets, the kind that are left underneath fish and lifted up, were not used until Milerum’s time, and even then they weren’t used very often.

The kalatar ‘fish trap basket’ pictured below was used for trapping small fish in flowing swamps. The kalatar was used in conjunction with fish trap walls.

Urti! ‘Deadly!’ Now let’s look at some fish and crustaceans commonly caught in the region

Fish and crustaceans

Let’s learn some sentences using these fishing words.

matjurunu means ‘father’, wayenu means ‘older brother’ and turukun means ‘diving for mussels’.

kardarangku means ‘fishing net’ and warra means ‘bring!’

nandurrar means ‘men’, meiminar means ‘women’, the ending -il shows that the men and women are doing the action of the sentence, nganangkuri means ‘fish trap wall’ and ngarrun means ‘making, building’.

donggari means ‘mulloway’, thakun means ‘to eat’ and ngankuri means ‘good’.